Once Upon A Time in Tech(June 2019)

Part 1 - Software Mania high level

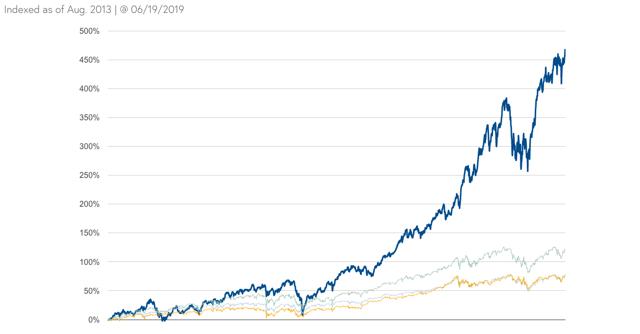

Bessemer Emerging Cloud Index is up 470% since Aug. 2013 with 60% of that performance occurring over last year.

Median EV/Sales Multiple has nearly quintupled from Feb. 8, 2016 low, and is now roughly 3x trailing ten-year avg:

Median EV/TTM REV SAAS/CLOUD | |

Q4 2008 Low | 2.1x |

Q1 2014 Peak | 7.4x |

Q1 2016 Low | 3.1x |

2007-2017 Avg | 4.9x |

Today | 14.2x |

Here is how the 2013/2014 SAAS All-Stars compare vs. there post LinkedIn/Tableau apocalypse Feb. 2016 lows:

2016 EV/NTM Rev | Guided Growth | 2019 EV/NTM Rev | Guided Growth | |

Salesforce.com | 4.6x | 21% | 8.2x | 21% |

Workday | 5.7x | 35% | 15.4x | 26% |

ServiceNow | 5.4x | 35% | 16x | 31% |

NetSuite | 4.9x | 30% | Acquired | |

Ultimate | 6.2x | 25% | Acquired | |

Splunk | 4.3x | 30% | 8.6x | 22% |

Veeva | 4.9x | 25% | 24x | 19% |

Tableau | 2.5x | 29% | Acquired (7.8x) | 18% |

Medidata | 3.8x | 18% | Acquired (10.9x) | 16% |

Cornerstone | 3.4x | 28% | 5.6x | 5% |

There are now 20+ SAAS names trading over 15x trailing EV-to-sales, and 15+ names trading over 20x trailing EV-to-sales.

To put this in perspective

Salesforce (NYSE:CRM) from $1bl to $13bl in revenue over past decade has traded in 2.3x-12.5x EV/TTM revenue range with an average of roughly 7x.

At its early 2014 peak, Workday (NASDAQ:WDAY) sported a 30x trailing multiple on the back of a roughly 100% growth rate. Over the next four years, it took shareholders to break even Workday’s trailing revenue growth rates were 72%, 69%, 48%, 36%, and 36%.

How about some 2000 Software compares?

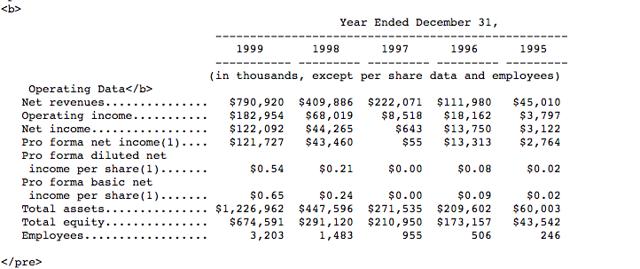

Here is a snapshot from Siebel’s 2000 10k:

You can see the company averaged roughly 100% growth over the late '90s run. It peaked at roughly 28x sales and 150x earnings in early 2000.

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT) hit a market cap of roughly $660 billion in early 2000, which was 27x EV/sales multiple. Oracle (NYSE:ORCL) topped out in a similar range. For those wondering what Microsoft’s stickiness at the top works out to their market cap has grown at roughly 2% CAGR over last 19 years as revenues have grown at about 8.5%.

So, are we in Software/Cloud Bubble? The bird’s eye view definitely offers enough evidence for those looking to make such a case, but I don’t think its conclusive. There are clearly inefficiencies out there in the space, but a closer examination is warranted. Time for a trip down tech bubble memory lane….

A Brief History of Cloud Computing and Tech Bubbles

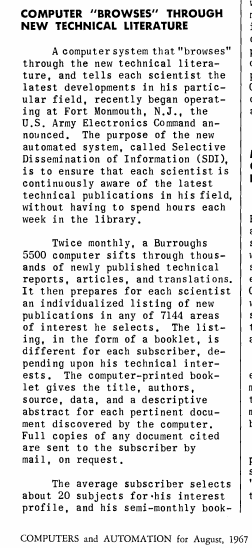

Before I get into the new paradigm in software, I thought it would be best to take a brief trip down memory lane. The following is an excerpt from an article written by Manley Irwin titled, “The Computer Utility: Competition or Regulation?” It was published in the Yale Law Journal in 1967:

Within the decade, electronic data centers will provide computational power to the general public in a way somewhat analogous to today's distribution of electricity. Computer systems will blanket the United States, establishing an informational grid to permit the mass storage, processing, and consumption of a variety of data services: computer-aided instruction, medical information, marketing research, stock market information, airline and hotel reservations, banking by phone to mention only a few.Many of these services already exist in embryonic form; and their growth prospects have received enormous impetus from recent developments in computer technology known as time-sharing or multiple access computer systems. Time-sharing permits several users at remote locations to have access to or to share computer memory and logic capability. Under the traditional batch processing method, access to the computer was limited to one user at a time, although even the most complex scientific problems consumed less than 10% of the computer's capacity. This kept data-processing charges high and limited the market for computer services. Multiple access computers make it possible to soak up this excess capacity. Indeed, computer power may experience such drastic cost reductions that it will be priced as low as, say, electricity.

Data processing firms can be classified as: (1) integrated firms that manufacture computers and peripheral devices and also offer data processing services; (2) nonintegrated firms that manufacture a variety of terminal equipment; (3) nonintegrated firms offering only data processing (service bureaus); and (4) corporations that sell data processing services as a sideline because of excess computer capacity. The first group, computer manufacturers, includes some dozen hardware fabricators which also operate data processing centers or service bureau affiliates. These main-frame fabricators compete in a separate market with suppliers of peripheral hardware, such as desk-size computers, video display devices, printers, readers, data sets (modems), tape drives, and others. The service bureau market is made up of firms that buy and lease computer hardware, and sell machine time or data processing to their subscribers. In contrast to the concentrated computer manufacturing market, about 800 firms engage in service bureau activities, suggesting that market entry into this phase of data processing is relatively easy. Many of these firms operate locally or regionally. Finally, the data processing field is inhabited by firms whose activities are ancillary to data processing per se. These firms, having computerized their in-house data requirements, use up excess capacity and reduce overhead by expanding into commercial data processing. The banking and aerospace industries are particularly important in this sector of the market. Even the fully-integrated data processing firms lack the communications circuits that will be an essential part of a national information system. This makes the communications common carriers prime candidates for entry into the information utility field.

What is the projected growth of computer utility services? The evidence tends to be fragmented. Some project that by 1970, sales of timeshared services will approach 2 to 5 billion dollars; others assert that 75 per cent of all computers will possess time-shared capability by 1970 and by 1975, 90 per cent of all computers will be on-line; others project that within five years over 50 per cent of all computers will be tied directly into the nation's communications lines; and finally, still others maintain that, within the same time period, over half of the nation's communications will be transmitted as data rather than by voice. If the growth of the data utility approaches the estimated rate, it will bring the data processing and the communication industries into unprecedented intimacy.

Pretty crazy right?

If we postpone consideration of IBM as a special case, the remaining major computer manufacturers generally inhabit two markets: manufacturing computer hardware and operating data processing centers competitive with those of independent service bureau firms. It is the existence of many independent service bureaus that gives the data processing market a semblance of workable competition, but their survival is precarious in a market where size and integration are at a premium. Except for the companies that operate a service bureau as a sideline to use up excess capacity, the non-integrated firms must write off the full retail price of a computer with their service bureau revenues. The hardware manufacturers, using their own machines at a much reduced shadow price, can afford to operate on a smaller margin over variable costs. Similarly, the advantages of specialization attach, not to a firm that is small and local, but to a large company that can spread the costs of specialized software over a large volume of business. Caught in a cost-price squeeze, the non-affiliated service firm may choose among several options: they could merge with a hardware supplier and become similarly integrated; play off one supplier's price against another's; merge into larger service bureau units in order to establish countervailing power, or get out of the industry altogether. IBM is, of course, unique, not only because of its predominance as an integrated supplier, but also because it must live within the constraints of an antitrust consent decree. The 1956 decree ruled that the parent manufacturing firm could not engage in service bureau activities in which customer data is manipulated or otherwise changed. The decree sought to split IBM as a manufacturer and IBM as a service bureau. To this end, the Justice Department required IBM to form the Service Bureau Corporation, a separate data processing affiliate," and run it as an independent business. But the decree did not condemn IBM's own machines to idleness. Today, subscribers may bring their data to IBM's own data centers, process it, and be billed for the appropriate machine time. Because IBM does not "touch" customer data, the sale of raw machine time is ostensibly a legitimate activity under the consent judgment. IBM not only manufactures time-shared computers, but operates time-shared data centers as well. With the Quicktran service, for example, IBM computer centers will offer facilities for solution of engineering and scientific problems by subscribers who are located at remote stations. In addition to its market information service, IBM recently inaugurated a time-shared service that edits, updates, and justifies correspondence, reports and other business documents." Again the user gains computer access via a remote terminal.

These new developments in technology and services raise the question, once again, of the status of IBM's consent decree. Does timesharing merely put IBM in the business of selling computer time over telephone lines or is IBM processing customer data for a fee? The answer to this question is not clear; but as if to hedge its short term antitrust bet, both the Service Bureau Corporation and IBM, the parent corporation, have recently introduced nationwide systems of time-shared computer centers. In the long run, however, IBM may find it necessary to convince the Justice Department that new technology has invalidated the distinction underlying its 1956 judgment.

Does 2019 AWS remind anyone of 1967 IBM (NYSE:IBM)? Do the regulatory concerns regarding the ‘touching of data’ sound familiar? I dug up this gem because the current investment climate echoes the mania of the computer leasing bubble of the go-go late 1960’s stock market.

Mad Men

To fully grasp the tech bubble of the late 1960s, one simply needs to look back at the IBM Mainframe-dominated era of computing. By 1968, an investor who purchased shares in IBM at the end of WWII had watched his investment grow nearly 120x. As investors went looking for the next IBM, the prohibitive hardware costs of mainframe computers spawned a new industry computer time-sharing. Companies like Rapidata and Tymshare allowed users to rent computer access by the hour using telephone lines. Hot leasing stocks like Leasco Data Processing Computing and Levin-Townsend Computers reached multi-billion-dollar valuations on the back of business models that simply involved leasing IBM 360/85 Systems for 10-20% less than what IBM would lease them at. Did the economics of slightly undercutting IBM on leasing work? Obviously not, as both these names eventually went bankrupt, but that didn’t stop investors from believing they might one day. But the time-sharing boom did open the flood gates to a broader tech mania and the wonders of tech/data enabled services that could be offered by the increased access to super-computing power.

Here are some of my favorites….

A 1967 version of Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL) (NASDAQ:GOOG):

A NASA Apollo engineer-backed computerized ticketing service for cultural/theatrical/sport events:

An early version of Survey-Monkey and a company using cloud hosting of architectural designs for buildings to cut costs:

And, here is my favorite headline, which has nothing to do with innovation; rather, data-processing firms were suing the OCC to prevent big banks from entering their market because ‘their large financial resources can subsidize profitless operations in data processing’.

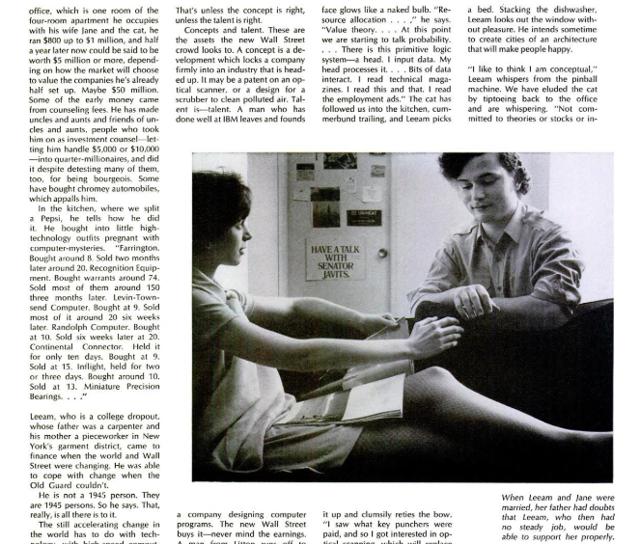

Then, you have the wunderkind stories of the ‘GO-GO’ market like this June, 1969 Life Magazine feature on 23-year-old tech stock genius Leeam Lowin:

The best part of the article can be found in the 2nd paragraph of this clip:

Not surprisingly, boy wonder stock pickers led to boy wonder-esque business models. No company encapsulates this better than National Student Marketing Corporation. Essentially, a ‘chain letter’ marketing platform (think mass-email or marketing automation today), NSMC promised to unleash the power of mass marketing by leveraging its ‘secret sauce’ of nearly 1,000 part-time college students. The stock IPO’d at $6. At its peak, it traded to $140. What turbocharged the shares? NSMC’s decision to acquire an insurance company to leverage its student marketing platform.

But technology mania can’t last forever, and like all bubbles before and after, the Go-Go market eventually came to an end.

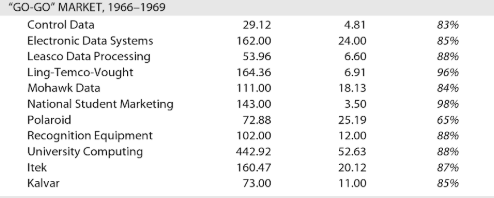

This is how some of the high flyers fared when all was said and done:

By the time the bubble had burst, the only companies to come out on the other end were the ones that had built sticky services around their offerings like IBM and ADP (NASDAQ:ADP). Yes, long before Workday, ADP was effectively a cloud HR SAAS. What changed?

The PC Blah Blah

"Hello, I'm Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag. Unaccustomed as I am to public speaking, I'd like to share with you a maxim I thought of the first time I met an IBM mainframe. NEVER TRUST A COMPUTER YOU CAN'T LIFT."- Mac Intro 1984

The PC ushered in a new era in computing and delivered the final death blow to the time-sharing model. Data processing could now be handled in house by all corporations, and hardware was all the rage. Unlike the late 1960’s mania, the potential of services and software took an early backseat to the power of transformative PC. Software was simply a tool to enable the PC which at the end of the day was viewed as the end product. This view was so deeply rooted at the time that industry giant IBM decided to outsource the development of their operating system on a non-exclusive basis to a company founded by this guy:

When Microsoft listed in 1986, the company was worth $650 million, while, IBM, its marquee customer for PC OS licenses, was worth over $90 billion. The era of licensing enterprise software as the most lucrative business model in technology had begun. Over the next ten years, Microsoft would ride Windows and Office and surpass IBM in market value. Software was king. But naturally, right about the time, Microsoft had dethroned Big Blue, a company led by a 24-year-old named Marc Andreessen was about to shake things up.

Netscape went public on August 9th, 1995; the technology era of the internet had officially begun. PC and software now took a back seat to internet infrastructure build-out companies like Nortel, Lucent, and Sun Microsystems. The proliferation of network and affordable enterprise web infrastructure hardware, combined with the web browser, meant that hosted services that had been dreamt of in the late '60s were now possible. E-commerce, Internet Service Providers, and Search engine companies exploded on the scene. But while traditional enterprise software companies were no longer the star of the show, their models continued to flourish throughout the late '90s as enterprise IT departments exploded. Microsoft managed to kill Netscape and take over the web-browser market, and companies like Oracle and Siebel prospered selling ERP and CRM software throughout the boom.

But while replacing lucrative licensing of enterprise software companies with web-hosted services model seemed a bit premature, internet mania ensured at least a few entrepreneurs would take a crack at it. Near the end of 1998, NetSuite was founded to sell web-hosted accounting software. A few months later Saleforce.com was founded to take the same approach in CRM software. Oracle’s Larry Ellison was an investor in both companies, presumably because he believed that these companies may grow quickly selling more affordable enterprise software as a service to young startups lacking the financial resources to purchase Oracle’s on-premise applications. He was hedging his bets, and the initial traction both companies achieved seemed to show his investments would bear fruit.

Pop(stars)

However, just as SAAS was emerging from the womb, the tech bubble burst. Companies like Salesforce.com saw most of their initial target customer base quickly start to go out of business. Survival replaced disruption as a top startup priority, and ironically for the young cloud upstart, this proved to be a good thing. There is a silver lining to making it through a massive storm……

The burst of the tech bubble doesn’t get the credit it deserves for essentially creating some of today’s most successful ‘tech’ companies. Collapsing bandwidth prices, compute infrastructure hardware resources, and access to tech human capital costs played a huge part in creating today’s giants. Consider that up until 2005, nearly 85% of broadband capacity in the US was idle. Could Google have thrived or Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX) have built a streaming business without this idle infrastructure? It’s like asking whether Uber could have ever scaled without AWS and Google Maps, both byproducts of the type of long-term differentiating investments tech bubble survivors were able to make.

Even Salesforce.com benefited from the crash. While it at first felt the pressure of the collapse of its core startup customer base, its main competitor Siebel was hit even harder. At the peak of the bubble, more than 2/3 of Siebel’s revenue came from their call-center business. The big clients here were telcos that were hit the hardest when the bubble burst. And as enterprises gutted IT staff, the value proposition of subscription CRM as an alternative to expensive on-site deployments only grew more compelling. Yes, security was still a decent concern, but recession-induced cost cutting opened the cracks enough for the likes of Salesforce.com to start growing again.

Post-bubble consolidation is another often forgotten catalyst that helped the cloud model. Companies like Oracle acquiring the likes of Siebel and PeopleSoft provided integration distractions and new pools of software talent for cloud upstarts to utilize.

However, while the tech wreck may have laid the foundation for cloud, its main carnage localized in the new economy. What really allowed the cloud model to take off was this….

The financial crisis probably was the single best thing that ever happened to the cloud tech leaders. As the traditional economy took it on the chin globally, cost-cutting became a big focus for all enterprises. Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) would not be what it is today if the crisis had not occurred. On one end, the crisis wreaked havoc on all the company’s traditional brick and mortar retail competition; simultaneously, the crisis was driving companies that had never considered hosting their IT infrastructure in the cloud towards Amazon’s lucrative AWS business.

Netflix was another big winner. The crisis meant consumers were looking for cheaper alternatives to cable, while cable content providers were looking for more revenue. The is how a company like Starz thought pocketing an extra $25 million licensing its vast OVD library to a streaming upstart made good business sense, and how temporary cost saving turned into cord-cutting. Today, Fintech startups and ‘tech payment’ companies that make money by essentially originating SMB loans can also credit the financial crisis for incubating their business models.

Anyway, that’s enough history for now - I’m sure I’ve already lost 80% of the Twitter generation. But if you made it this far, you should come away with three main takeaways from this trip down Cloud/Bubble Tech memory lane.

There is a virtuous cycle of insourcing/outsourcing that permeates all businesses, let alone the technology sector. When this never-ending cycle is packaged as some sort of new paradigm, you should reach for the history books. Is it really a stretch to compare today’s Amazon to IBM and time-share computing in the 1960s? You may argue that Amazon doesn’t manufacture mainframes, but is that really the case? If you are designing your own semiconductors/networking equipment/database management tools, etc., you are in effect sourcing components to build supercomputing capacity few others can achieve. Thereafter, you can rent infrastructure and layered services to others based on that moat, which means IBM’s service bureau business of the 1960s is not much different from what AWS is today.

As a catalyst for innovation, economic disruption is rarely given the credit it deserves. Most of the best new economy businesses are byproducts of major macroeconomic disruptions. The perception that new tech companies, especially in tech-enabled services, are about building a better mousetrap can be very misleading.

As it has been a decade since the financial crisis and nearly two since the tech bubble burst, I’d argue that many of today’s anointed tech “disruptors” are doing little in the way of true disruption. Companies whose models are thriving around access to abundant cheap capital, free data, aggregation, verticalization, and tech-enabled services built by outsourcing key technology components to other platforms deserve a healthy dose of skepticism. Being able to outspend your competitors on customer acquisition or beating them to market because you built your core product on top of half a dozen other microservices instead of engineering it yourself is not the type of environment in which an investor is likely to find the next Google or Amazon. Now onto the good stuff!!

Now on to the good stuff!

How Software Has Changed: The API Economy, Microservices, DevOps and SAAS 3.0

"The interesting thing about cloud computing is that we’ve redefined cloud computing to include everything that we already do. … The computer industry is the only industry that is more fashion-driven than women’s fashion. Maybe I’m an idiot, but I have no idea what anyone is talking about. What is it? It’s complete gibberish. It’s insane. When is this idiocy going to stop?" – Larry Ellison, 2008

While a decade ago, the terms SAAS and Cloud may have frustrated Larry Ellison, there is no denying they are now the norm in software. When investors used to get excited about a SAAS company, they typically would be describing a hosted multi-tenant subscription-billed piece of software that was replacing a ‘legacy’ on-premise perpetual license solution in the same target market (i.e. ERP, HCM, CRM, etc.). Today, the terms SAAS and Cloud essentially describe the business models of every single public software company. Therefore, understanding the market’s current infatuation with software companies requires taking a closer look at how software development has changed.

The Rise of Microservices

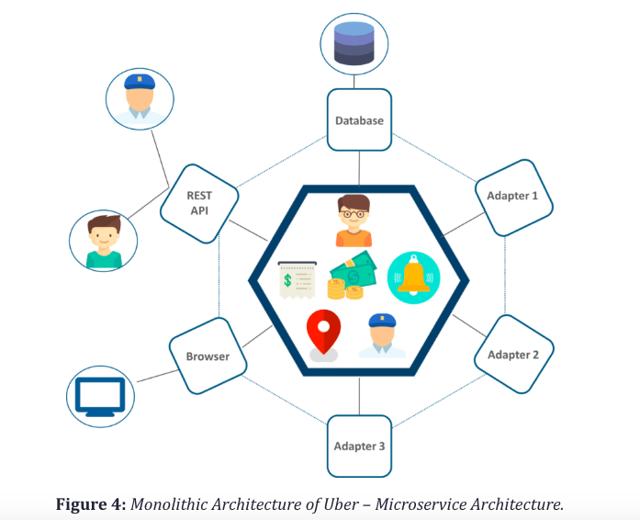

The legacy on-premise era is often associated with a monolithic architecture approach to software development. A monolithic application consists of a single unified code base written in one language that puts all its functionality into a single process. It typically uses one database, and scales by replicating the entire monolith across multiple servers. This contrasts with a microservices approach….

“The microservice architectural style is an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API. These services are built around business capabilities and independently deployable by fully automated deployment machinery. There is a bare minimum of centralized management of these services, which may be written in different programming languages and use different data storage technologies.” - Martin Fowler

The limitations of the monolithic model are pretty clear on the surface - most notably, that any small change or update requires deploying an entirely new version of the application. This architecture was suited to the era of perpetual license software as companies could invest the time and expense to release new software editions every couple of years. It does however pose challenges in the cloud/on-demand environment, which is characterized by continuous integration and rapid deployment.

Here is a table depicting some of the key differences between the two architectures:

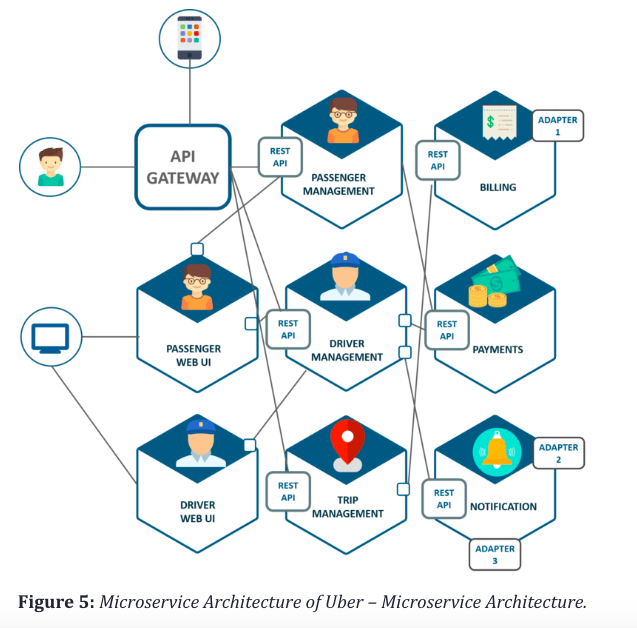

An often-cited poster-child for the microservices approach is Uber.

Here is what Uber’s monolithic architecture looked like when they were operating in a single city:

And here is what Uber’s architecture looks like after adopting a microservices architecture:

Now, I’m no software engineer, so I’m not going to dive any deeper into the technological merits of each approach. What works well for companies at the scale of Uber or Netflix may not suit most startups. But acknowledging the rapid rise of microservices architecture is necessary for anyone looking to comprehend the current dominant investment themes in software.

The API Economy

The Uber example of how a company divides its application architecture into several narrowly defined business functions is at the heart of what is now being referred to as ‘The API Economy.’ An Application Programming Interface (API) is a set of programming instructions and standards used for accessing a web-based software application or tool. A software developer would probably simply describe it as an http request. The term has been around for a long time and can refer to internal application/data communication tools, external third-party resources, and can be public or private. What’s changed recently is how the term is interlinked with business models in technology, specifically, those of companies that provide narrowly defined business function services that are consumed in the form of a 3rd party API.

Uber is a ride sharing service. When you use their application, the action you are taking is simply booking ride. But that action consists of many distinct business functions: maps that connect you and the driver, payment processing to pay for the ride, push notifications to know when your ride is arriving, and anonymized calling for you and the driver to be able to communicate if need be. Uber, which has architected its platform in a microservices manner to be able to massively scale, hasn’t built all this functionality on its own. The maps come from Google, the payment processing from Stripe and Braintree, and the telephony from the likes of Twilio (NYSE:TWLO) and Nexmo. All this functionality is built into Uber’s application by developers who integrate these companies’ APIs. Call it ‘digital outsourcing’ or the ‘operationalization of software’; either way, you are dealing with narrowly defined business process service specialists. These companies are modern day service bureaus with the notable distinction being that their services are exposed in real-time through web calls.

As for the ‘API Economy’ jargon, every new investing theme needs a nice marketing buzz-word. What this term means to me is that the idea of building a multi-billion-dollar business by writing a very thin piece of software to expose one back-end business process for other application developers to consume, which would have seemed farfetched to most developers even just a decade ago is all the rage today.

Here are a few companies with an API-first product strategy:

Stripe - payment processing

Twilio - SMS/Voice telephony

SendGrid (now part of Twilio) - Email delivery

Plaid - bank accounts

Algolia - search delivery

Twilio is currently the only publicly listed name in this group, and from a market standpoint has been the trail blazer of the bunch. Their CPAAS business model is essentially about powering the telephony of an application via the integration of their API. Like most API-first success stories Twilio’s utility centers around layering some value- added services (sms/voice delivery, anonymized calling, two-factor authentication) on top of aggregation in a fragmented market (global telco carriers). For an on-demand services provider like Uber or Doordash, integrating Twilio’s API’s is tantamount to switching on a virtual dispatch operator. Instead of purchasing cb’s, multiple phone lines, negotiating local and long-distance rates with a telco, and hiring dispatch operators; you can simply integrate an API pay a consumption-based fee. To be clear though, developing a telecom application server with value added services on top of carrier aggregation isn’t exactly a new business model.

So, what are the likes of Twilio doing differently?

The short answer to this question is they have adopted a developer first go to market strategy. This means the secret sauce here is developer evangelism, SEO spend, and great API documentation and support. This is how you turn a commodity 50% gross margin biz into a 20x sales $17bl company. Will Twilio ever achieve meaningful profitability? That remains to be seen. However, with everyone in telecom IT services now referring to themselves as CPAAS providers, it’s no surprise VCs have become obsessed with finding the next Twilio or Stripe of X.

DevOps Utility Belt Suppliers

The proliferation of microservices architecture means that most application are now highly distributed systems. Consequently, from an IT standpoint, monitoring these systems is now much more of a critical issue. This has created a whole new wave of tech specialist companies who provide tools for DevOps.

Application performance and infrastructure monitoring companies provide software which essentially surfaces critical performance data/issues in the form of alerts. Notable names here include New Relic (NYSE:NEWR), Nagios, App Dynamics, Datadog, Splunk (NASDAQ:SPLK), and Dynatrace.

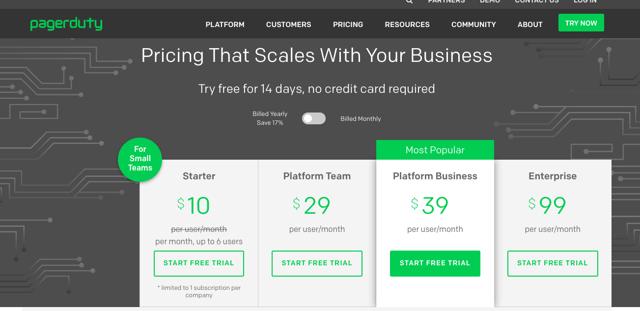

There are on-call management companies like new IPO darling PagerDuty (NYSE:PD) and Opsgenie which take alerts and route them to site-reliability engineers based on defined incident escalation protocols.

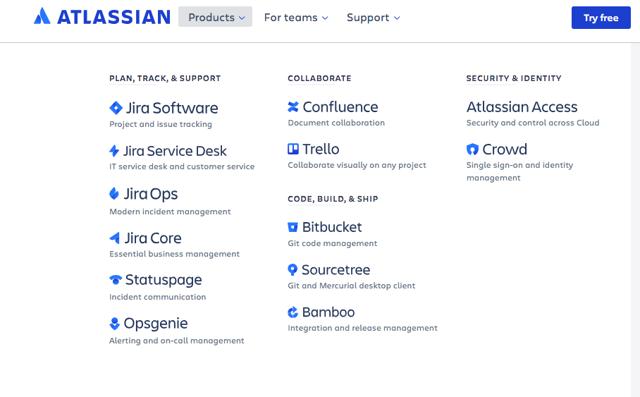

And with applications being developed and maintained in a highly distributed manner, you have companies that have become very successful by providing issue tracking and collaboration tools like Slack (NYSE:WORK) and Atlassian (NASDAQ:TEAM).

At the sector level, you are going to have a tough time finding any reasons to dislike this space. They are the pick axe and shovel providers to IT Ops of all enterprises.

The Disruptor’s Economic Dilemma

There is no shortage of coverage on all the benefits of the new paradigm in software. Disruption and innovation are always exciting, but when you change how ‘software’ companies are built. there are long-term economic implications that need to be considered.

Moats Are Not What They Used To Be

I mentioned PagerDuty as an example of a great success story in the SAAS 3.0 space. They just went public and trade $3+bl 30x+ revenue valuation. PagerDuty is an on-call management SAAS provider. Basically, when there is an IT incident their software routes/pages the on-call DevOps team members responsible in a pre-defined escalation manner. This means the service sits below Application Monitoring and Infrastructure monitoring providers like Splunk, Datadog, New Relic and above a telephony enabling microservice like Twilio. At the same time, it can also plug into issue tracking/collaboration/ITSM provider tool providers like Atlassian, Slack, and ServiceNow (NYSE:NOW). It’s about as thin of an application as you could think of, and that’s why the gross margins are already 85%. They are automating the on-call process by essentially enabling telephony escalation when needed. How is this done?

Simple, they leveraged Twilio.

A rock-solid telecommunications service was crucial to PagerDuty’s success, which is why the team selected Twilio as their primary provider. “We absolutely cannot go down,” said Owen Kim, one of PagerDuty’s lead engineers.

Twilio also offered the flexibility of escalating from SMS to voice notifications, as well as a very straightforward API that eased the pain of integrating PagerDuty with monitoring services like Nagios, Pingdom, Splunk, and Zenoss. “The Twilio integration was one of the easiest I have ever done,” Kim said.

Where Twilio aggregates carriers, PagerDuty aggregates incidents and then leverages Twilio’s communication platform to route the alerts. This is microservices at its best. The only issue here is the barriers to entry are so low that competitors like VictorOps, OpsGenie, xMatters, Everbridge (NASDAQ:EVBG) etc. are all chasing the same thing.

Here is competitor VictorOps touting how it leveraged Twilio:

VictorOps’ build with Twilio Functions took one engineering team member approximately two weeks to build in JavaScript. After just one week, the prototype was ready. Nate estimates VictorOps saved $60,000 in engineering hours, compared to building the same solution with Twilio Functions alternatives.

And here is ServiceNow touting how it built a plugin to provide similar functionality for its customers:

With the Twilio integration, bidirectional voice and SMS is just a click away - capabilities that previously required hardware components and a contract with a telco provider. Said Pope,

“I press a button, the message smartly gets to Singapore and the right person, and I get a response back. That’s it. I don't have to worry if I'm working with Verizon, AT&T, BT or any carrier for that matter—that’s Twilio’s problem.” said Pope. “So it was almost a no-brainer.”

Keeping it simple is the other component to customer adoption. “Our users fill out a form with their credentials and behind the scenes we’ve connected it to Twilio and they deliver the voice and SMS anywhere in the world,” explained Pope.

“We get a response back in terms of delivery. If it’s an escalation, we get a response back from the user. We made a framework that is simple and easy to use, and our customers don’t know that behind the scenes it’s Twilio, which is what makes it even more powerful.”

Consider that Twilio is a $17billion market cap company that only did roughly 5x PagerDuty’s revenue last year. Its gross margins are 54% vs. PagerDuty’s 85%. You think they may want to climb up the application stack and cut out the likes of PagerDuty which is getting per seat pricing of roughly $30 per user a month?

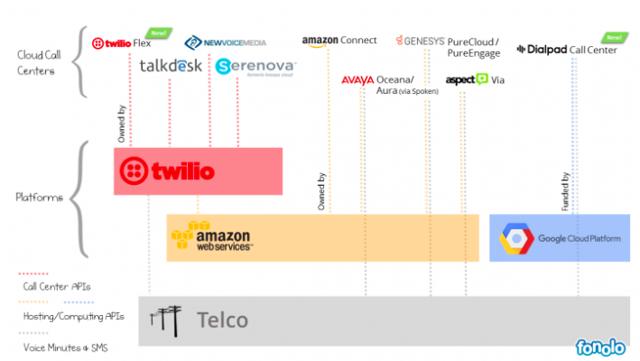

To answer this question let’s take a quick look at the contact center as a service space.

CCAAS

The call center has been dominated by legacy providers like Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO), Avaya (NYSE:AVYA), and Genesys who pretty much conquered this segment about a decade ago. As with all things cloud vs. legacy, the last few years has seen native cloud players chip away at the call center. The space has been dubbed CCAAS. A year ago, the notable disruptors were differentiating themselves from the legacy providers by leveraging Twilio’s API. Then Twilio introduced Flex.

Here is a snapshot of what the landscape looks like today:

When Flex was introduced last March, Twilio was mum on pricing and two of these CCAAS customers put a good spin on the announcement. Twilio also made significant efforts in showing (spinning) how they are not a competitor here with help desk customers like Zendesk (NYSE:ZEN) as well. But when Twilio Flex pricing was announced it consisted of both per-hour-per user and per month per seat options. That’s direct competition, and Twilio has already announced Shopify and Lyft as early adopters.

Twilio has no choice but to climb up the application stack. This is a company whose ‘disruption’ is essentially great API documentation and gangbuster SEO spend built on top of a highly commoditized telephony aggregation API. They have won by marketing to DevOps engineers. With all the hype around them, you’d think Twilio invented the telephony API, when in reality what they did was turn it into a product company. Nobody had thought of doing this let alone that this could turn into a $17 billion company because simply put the economics don’t work. And to be clear they still don’t. But Twilio’s genius CEO clearly gets this. If the market is going to value robocalls, emergency sms notifications, on-call pages, and carrier fee passed through related revenue growth in the same way it does ‘subscription’ revenue from Atlassian or ServiceNow, then take advantage of it while it lasts. That’s why he launched Flex and acquired SendGrid for nearly a third of Twilio’s market value six months ago at half its current share price. He realizes he needs a higher margin sticky enterprise application beachhead (and make no mistake Twilio is making progress here) before the DevOps bubble pops and engineering labor costs all of a sudden make building or shopping around a no brainer value proposition. So, don’t be surprised if Twilio develops or acquires an on-call management product sometime in the near future.

These moat related developments are naturally impacting the investment landscape. After Flex was announced, NewVoice Media’s CEO was quick to say they don’t use Twilio for telecom. Six months later, they sold to Vonage for less than 4x forward revenue. TalkDesk has gone in the other direction. They introduced a ‘bring your own carrier’ option in their enterprise CCAAS offering, and they recently raised $100 million at $1 billion valuation. This is 5x the capital they have raised so far for a company that was essentially a Twilio hackathon project. And several other Twilio customers recently chimed in on Flex at Twilio’s Oct 2018 Signal conference…

“We built our own Twilio Flex, before Twilio Flex even existed.” – William Syms, Momentum Travel Group

“We built Flex, basically.” – Eugene Kovnatsky, Centerfield

“For us, using Flex hasn’t been an option. We have a common front-end that we use for ING for both web and internal applications. That’s a reason to stick with our own platform.” – Jeroen Visser, ING

With Twilio now a direct competitor to many of its existing customers, you now have a build vs. buy debate taking shape. Twilio has already seen large customers like Uber diversify away from their core offering, which makes the future success of Flex all the more critical.

Which brings me back to PagerDuty…

Twilio is obviously an example of a threat from below, but in microservices, the threats can come from all sides. While PagerDuty just went public, several of its main pure play competitors have been acquired. VictorOps sold to Splunk for $120 million and OpsGenie decided to sell to Atlassian for $295 million. On one end, we have an actual application-monitoring leader integrating an on-call tool into its suite; on the other end, a project management and incident tracking DevOps leader doing the same.

While Splunk clearly hopes to leverage its own machine learning and big data to reduce the alert noise and provide an integrated solution from the top down, Atlassian’s master plan is a bit different.

Here is what its product stack now looks like:

Atlassian is clearly building the MS Office version of the DevOps suite, and in my personal opinion, I think they are well on their way to winning here. What started out as a project management tool is now a company that is essentially competing against Microsoft and ServiceNow. Its decision to stop competing against Slack and partner with them instead reflects management’s strategic approach. This doesn’t bode well for companies like PagerDuty because, ultimately, a company like Atlassian will be bundling on-call management as an integrated DevOps suite feature.

Relying on the Kindness of Strangers-Many ‘API Economy’ Business Models Have a Robustness Problem

The moat problem obviously implies less robust economic business model, but I tend to think of robustness more along the line of likelihood of complete failure. Abstraction has consequences, and in the ‘API Economy’ they can often prove fatal.

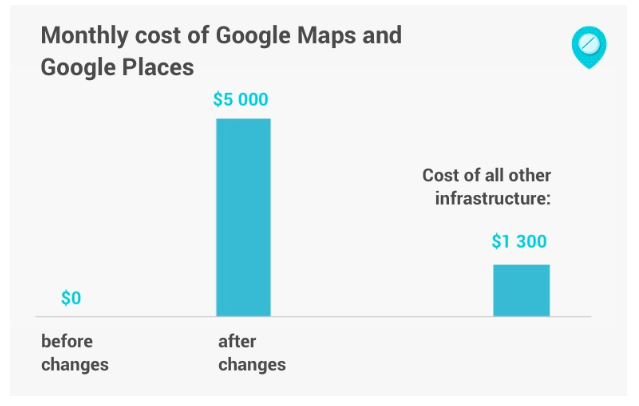

For all the hype around Twilio being an API product company disruptor, too little attention is paid to the world’s most widely adopted API-first utility service provider. Google Maps, as far as consumers are concerned, is a wonderful free utility product users regularly interact with on their devices. For developers and location-based services providers, it’s a critical piece of infrastructure that entire businesses are built on. There is literally an entire ecosystem of startups built around this core functionality. And in the ridesharing space, the rise of Uber as a microservices architecture company has been celebrated because of the likes of Google Maps, Twilio, and Stripe APIs allowing the company to scale and focus on its ‘core value proposition’ of enabling drivers and ride seekers to get matched. But providing high-level global integrated Maps is not exactly like enabling payments or voice/sms for location-based companies, it’s more of a core competency. For the longest time, Google made this API free for all but the most intense enterprise users, which were few and far between until the food delivery and ride sharing wave exploded.

That changed last year. Google Maps API now requires a private key and credit card for all users, and the pricing has skyrocketed. The web is littered with stories regarding mothballed projects and crushed models by this change, and for those with the time I suggest reading some of them. For the purposes of this piece, I’ll just focus on this one. Gdziepolek.pl (Polish for “where I get my meds”) connects patients to brick-and-mortar pharmacies so they can get their medicine. Google Maps is a core API for the product, and at their current scale had been free. This is what happened to their costs after the most recent price change:

This example is great because unlike many other customers who have complained of a nearly 15x increase, this customer is in the camp of many trying to scale location-based businesses that have gone from a cost of zero to something that basically invalidates their business model overnight. Naturally, they have had to seek alternatives, but as far as maps go there is nobody close to Google these days. They have switched to smaller competitors, but the issue there is that despite being cheaper they now actually have a mapping cost. This is because these competing map providers, unlike Google, have no other businesses. This is as things should be. As far as Google is concerned, these customers are nothing but a cost. They have lost no direct revenue, and if they don’t have capital to scale on their current product they likely don’t pose a long-term threat to the consumer side of the maps product which remains free. On the flip side, Google can continue to provide the world’s best product at a far superior value to any large scale location based service. Basically, Google was subsidizing a lot of unsustainable business models and that just ended. But ask yourself this, would Uber exist today if Google was already charging like this for maps? Is celebrating their microservice architecture model as impressive when viewed within this context? From a technology standpoint, what are Uber/Lyft when you strip away the rider subsidies? What does Google Maps/Waymo bring to the table in the future? And better yet, if Twilio is a $17bl standalone API product company, what would Google Maps be if it was spun out? Comparing mapping earth down to the last structure and actual street view over a decade to great developer friendly API documentation and carrier aggregation is almost comical; Google Maps should be worth 10-20x Twilio, which would be a $250 billion company.

And Google Maps is just one of many examples of what can go wrong when you build on the shoulder of giants. Remember Branchout? They raised $50 million to map a professional network through Facebook’s (NASDAQ:FB) API data and scraping LinkedIn. Both companies eventually blocked them, and Branchout was history (their assets actually were scooped up by a great startup scam called 1-page for those that want a good read check this out). Then there was live streaming video darling Meerkat which took off by leveraging Twitter’s Opengraph API. When Twitter bought competitor Periscope, they got all of two hours' notice informing them they were now in violation of Twitter’s term of service and would need to change the product. What about Imgur who built a business off of hosting images on Reddit up until Reddit decided they would do that themselves? Or Criteo in adtech today as it waits for Google to make up its mind on what it will do with Chrome third party cookies? Low level abstraction of compute and storage is one thing, but clearly as you go up the chain you are sacrificing robustness in your business model.

I also think if you look closely at what is celebrated today as innovation you often find models built on hidden subsidies. The USPS subsidized Netflix’s DVD mail business. The collapse of hardware infrastructure and bandwidth costs post the tech bubble made AWS and Netflix Streaming viable (a pretty bad sub licensing deal by Starz also helped Netflix). Google Search subsidizing mapping and Apple driving the proliferation of the smartphone are what made location-based services feasible. The financial crisis also played a big part in all of this as it accelerated the AWS model as corporations looked to cut cost which further drove down infrastructure costs just around the same time that capital became cheap. But Netflix, Apple’s iPhone and Google Maps' recent price increases, while different, are still stark reminders that the most robust models are few and far between. The hyperscale giants continue to vertically integrate into semiconductors, networking equipment, and storage and server equipment design while simultaneously plowing ahead at more high-level application functionality; where is the ceiling of their ambitions? Are we going to reach a point where these companies will require a regulatory compact like public utilities? Or are we already there? Though I wouldn’t hold my breath with the DOJ busy sending letters to the Academy warning them not to discriminate against streaming content while Google Maps API just went up 1500% and a high-end iPhone is 3x what it cost in 2007. Anyway, I think I have digressed enough, back to the issue at hand.

The TAM Problem

TAMs are always an interesting area of focus when you have a wave of IPO’s. In fact, I’d argue the very distributed nature of microservices architecture and API-first product companies means addressable market sizes and unit economics assumptions should be even more carefully scrutinized. Interestingly enough, the best way to illustrate the TAM problem facing many of today’s new software darlings is by revisiting one of the last SAAS IPO mania’s greatest success stories.

The Curious Case of Veeva

I shorted Veeva (NYSE:VEEV) back in 2013 at roughly a $5bl market cap on a TAM thesis. I did extensive primary research on the CRM space and concluded Veeva’s $2bl CRM TAM was overstated by roughly 5x. As their life sciences enterprise content management and MDM products had negligible revenue at the time, I found the thesis to be quite compelling. The short worked out well. Fast forward a little over two years later, and I came back into the name at roughly its all-time low with a long-thesis. My thesis on CRM hadn’t changed all that much beyond acknowledging that competitive risks were not materializing anytime soon and thus they were well on their way to owning that entire market. What had changed though was that I felt they were now going to make rapid progress on the life sciences enterprise content management side, and that the market would pay up for this growth inflection. After the stock nearly doubled in less than a year, I moved to the sidelines. In the 25+ months since then, the stock has roughly tripled.

Now, here is the thing about Veeva...

My original assessment of the LS CRM market has proved spot on. Veeva’s Commercial Cloud subscription revenue grew 10% last year and is now just a hair under $400 million. This is at essentially total market penetration of what is now a in structural decline pharma rep space. You can even get a clearer picture of the lack of organic growth by tracking the fees Veeva pays to Salesforce.com for their CRM platform access. In the last year, those fees increased from roughly $66 million to $69 million. Seat growth in life sciences CRM is virtually non-existent. Veeva’s story in this space is about upselling add-ons to drive single-digit sub revenue growth. On a stand-alone basis, I don’t think you’d want to pay more than 5x sub revenue for this biz, and that’s setting aside the fact that IQVIA is now emerging as another Salesforce.com ISV in the vertical. That translates into a $2bl max market cap biz. This means net of cash and after a generous multiple for prof services revenue you are paying over 60x subscription revenue for the clinical side of their biz. And to be clear, if you added up all the life sciences spend across ECM/EDC/CTMS vendors, you’d have a hard time even cracking $2bl. Also, remember Veeva has to strip most of this revenue from life sciences clinical SAAS leader Medidata (NASDAQ:MDSO), which generally means this pie should organically shrink due to competition. Yet during Veeva’s most recent earnings call, the sell-side seemed so enamored with EDC prospects you’d think it was a complete greenfield opportunity and that Medidata did not exist. The next day Veeva added nearly ¾ of a Medidata in market value. Just a little irrational exuberance? If Veeva’s non-CRM subscription revenue got a generous 10x sales multiple you are looking at a stock with 65% downside. Thus, why bother looking at new software names when the case can be made that Veeva is the most richly valued name in Software.

How is this possible?

Personally, I think the best explanation is that quant models clearly like to overpay for Veeva’s margin profile regardless of the TAM element and shifting landscape dynamics. Basically, when you remove primary research from the investing equation, you end up with Veeva, a SAAS rule of 40 algo darling ticking time bomb waiting to go off. And there is a good rationale for why this is inevitable…

Meet Vlocity, i.e. Veeva 2.0

Vlocity is another Salesforce.com vertical CRM ISV targeting the communications and media, insurance and financial services, health, energy and utilities and government and nonprofit industries. It was founded in 2014 by ex-Siebel and early Veeva employees. They are saying they have recently hit a $100 million in revenue and are expecting to double that by the end of this year.

Here is an excerpt from the Techcrunch article on their recent capital raise and new-found unicorn status:

The idea he said was to build a company with a market that was 10x the size of life sciences. “What we’re doing now is building five Veevas at once. If you could buy a product already tailored to the needs of your industry, why wouldn’t you do that?,” Schmaier said.

That’s a nice elevator pitch. Now, my first question here considering their recent $60 million round was at a $1bl valuation, is why a triple digit growing Veeva clone with 10x the TAM is valuing itself at 5x forward revenue in this tape. If you are genuinely a vertical CRM with Salesforce on-board as an investor and platform provider, why would you raise capital at 5x forward sales when you are growing at 100% of an already significant $100ml revenue base? On the surface this is difficult to reconcile, that is until you consider there really can be no such thing as another true Veeva esque Salesforce CRM platform based vertical clone. This is because Salesforce.com will never again repeat the financial deal they cut with Veeva. If they wanted to do that, Veeva already exists and would be happy to oblige. Contrary to popular belief, Salesforce is not a member of the Veeva fan club. Salesforce didn’t invest in Veeva because they never believed they could accomplish what they did or that the markets would value them as they have. Frankly, I can only imagine what Marc Benioff thinks every time he looks at Veeva’s market cap. He just paid nearly $10bl less to acquire Tableau’s (NYSE:DATA) billion in revenue with tons of room to consolidate sales overhead than Veeva trades for.

But make no mistake, the Veeva story is remarkable. They only tapped into a few million dollars in capital to customize Salesforce.com CRM for pharma and rode Salesforce’s established decade worth of platform infrastructure investment right into the world’s 20 largest pharma companies. And for every CRM seat they sell, they charge pharma over 5x what they pay Salesforce to rent their platform access. Consequently, Veeva’s epic success story is just as much about Salesforce’s failure in the life sciences vertical with their own CRM sales strategy and the poorly structured economic terms of their Veeva value-added-reseller deal. Thus, if Vlocity could build five Veeva’s, they’d essentially be creating a company the size of Salesforce. I still remember when Veeva went public how often management used to throw around the $1.6 trillion life sciences industry number, targeting industries 10x that gets you close to US GDP. Which begs the question what’s left for Salesforce? Also, you are not really a vertical CRM specialist when you are targeting almost every other vertical but life sciences. At that point you are a horizontal CRM company, which is what Salesforce.com is already, or a consulting/implementation specialist like Accenture (NYSE:ACN) with subscription revenue model.

Which is why you can safely conclude Vlocity’s economic relationship with Salesforce is very different than Veeva’s. Does Salesforce.com get a slice of all subscription revenue vs. just a platform fee? I think so. Did Salesforce Ventures acquire a decent stake in the company? Yes. Do they likely have some sort of call-option on acquiring Vlocity? Yes, again. As far as Salesforce is concerned, the Veeva mistake is never to be repeated again which means investors really need to rethink what it means to try and create a cloud version of Siebel. The worst thing a platform application provider like Salesforce can do is allow a vertical specialist exclusive access to their platform. If you are Salesforce, you are clearly always better off keeping your platform as open as possible, and thus functioning more like a software arms dealer. That’s how AppExchange functions today. And when Salesforce determines that an app offers critical functionality that should be integrated into their platform, they acquire the company. We saw this with both Quip and Steelbrick. Thus, the odds of building a $3bl or let alone a $20bl market cap company on top of Salesforce’s platform are very low, and that’s why six years after Veeva went public the market is not littered with Salesforce based Veeva clones.

And if you are Veeva at this point, the entire future of your business model centers around products offerings for which you have built your own platform. This is somewhat ironic considering how often Veeva’s CEO and founder sets the industry cloud model story against his past platformization experiences. Without their own ECM platform Veeva would be nothing more than a white-label CRM provider in an organically shrinking market with an unsustainable relationship with their platform provider. At that point, would their decision to build their business model on-top of another company’s application platform be viewed as one of the greatest success stories in enterprise software history? It’s definitely debatable.

So, what’s my point here?

Today, there are 3500 apps listed on Salesforce’s AppExchange and probably close to 200,000 ISVs worldwide. Yet, there are only a handful of platform/infrastructure providers. So, in theory while accessing large TAM’s has become easier, the slice of the pie up for grabs has shrunk. This is occurring against a market backdrop that is valuing companies like this as poorly as they are presently valuing Veeva. This is not sustainable, and in my opinion the source of a potentially very lucrative playground for long/short passive investment opportunities.

SAAS 3.0 TAM Examples Worth Pondering

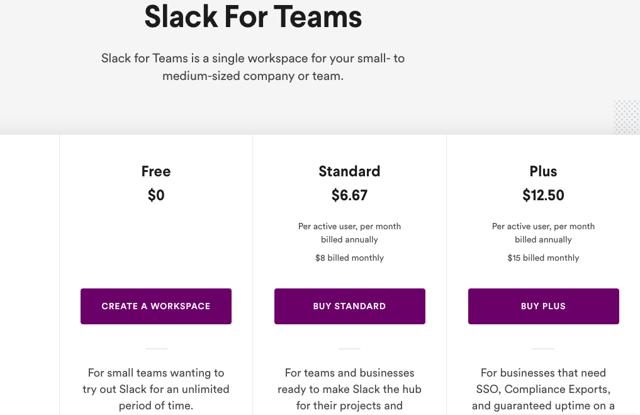

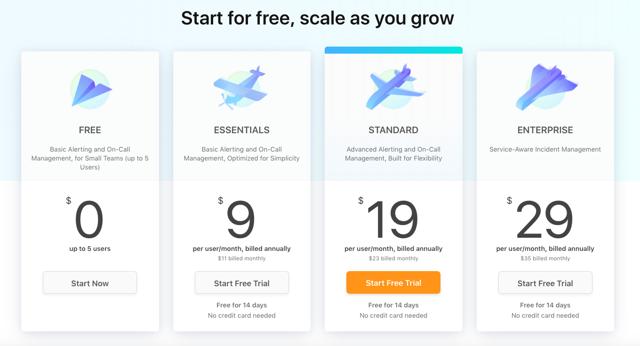

Slack and PagerDuty’s S1’s are two perfect examples of the TAM analysis challenges investors start to face at times like these. Slack lists their TAM at $28bl. PagerDuty lists theirs at $25bl. If you look at how both products are consumed, you can draw some interesting conclusions here. Once an alert is triggered a paged Site Reliability or DevOps Engineer typically hops onto Slack or Microsoft Teams to address the problem. You’d assume Slack’s TAM would be multiples of PagerDuty’s, and if you looked at paid users that would be reflected as Slack has more than 10x the paid subs of PagerDuty. But Slack and PagerDuty don’t price the same…

Here is PagerDuty’s pricing:

Now Slack:

PagerDuty has no free tier and is getting a $30+ ASP across its user base. Slack’s average revenue per user is about a third of that. But for PagerDuty users the key critical functionality is simply the delivery of a page, Slack’s role in the on-call incident management equation is far greater. Which raises the question of how sustainable PagerDuty’s pricing model is longer-term…

Here is Atlassian’s OpsGenie Pricing Model:

Now, Atlassian already has core products being used for incident resolution and project management, so at a core on-call functionality level you can conclude PagerDuty pricing has to converge to this level eventually. PagerDuty, naturally wants to add more functionality to their product so that they can increase pricing per user and not be viewed as just a very reliable critical alert delivery system. Of course, that’s what has made them very successful. Having talked to many users complicating the product is not something any of them are really interested in. So, to a degree, PagerDuty’s great success has been largely about pricing at a premium and getting away with constantly tweaking their pricing structures. But how sticky will that prove long-term? If Slack’s starting valuation is in the 30x revenue range how can they ever grow into it without bumping heads on incident tracking/oncall/video comms etc.

And if you are looking at comparable business productivity suites value propositions……

Microsoft Enterprise 365 Premium is $12.5 a user a month. That includes Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, Access, Teams, 1tb of OneDrive, Exchange, and SharePoint.

Google G Suite’s comparable offering is $12 a month and includes Gmail, Video +Voice conferencing, Messaging, Docs, Spreadsheets, Presentations, and unlimited storage, to name a few.

Bottom line: Digging into TAM assumptions right now around collaboration IT popular tools is probably well-worth the time.

Part Two: Signs of a Bubble?

Tangential Startup Boom: Financial Ecosystem/Business Model Related Plays Start to Grab Headlines

Late in a bubble, you start hearing more about businesses whose models are built around financially elements of the startup ecosystem or noticing that tech companies are actually deriving substantial revenue/cash flow by behaving like financial companies. Conversely, traditional financial companies start seeking more direct exposure or adopting elements of tech business models.

Consider the story of Brex, Ycombinator startup founded by two 22-year olds which has achieved Unicorn status in less than two years. Brex allows startups to get credit cards based on the amount of money in their corporate checking account. The argument for the business model is it solves a pain point for founders/principals needing to rely on personal credit to get their startups of the ground because the traditional banking system is less likely to extend credit to these companies. Of course, when you consider that each customer needs a corporate checking account with a minimum balance of $100k and that the balances are settled at the end of the month, one does start to wonder a bit about the pain points being addressed. And a month ago, Brex announced an ecommerce offering.

Here is how Brex for ecommerce is described:

The Brex Card for Ecommerce was designed specifically for online businesses with at least $50,000 in monthly sales that need longer payment cycles than the 30-day window offered by the Brex Card for Startups, says Michael Tannenbaum, Brex’s chief financial officer, in an email to NerdWallet.

“Brex saw lots of e-commerce companies signing up for its startup card (the Brex Card for Startups) but asking for longer payment terms to coincide with their ad financing and inventory financing cycles,” Tannenbaum said.

Unlike the Brex Card for Startups, the Brex Card for Ecommerce does not offer any rewards. But it can be a more appealing option for an online retailer who doesn’t want to incur the interest charges from a traditional small-business loan, but regularly needs a short-term cash infusion to maintain a steady supply of inventory and advertise its wares.

Now, easier access to financing and more flexible payment terms are the types of things typically associated with subprime financing, and in the cutthroat world of ecommerce business it’s no surprise that we are seeing more services tailored in this manner as making money of transaction volume isn’t easy. Shopify launched Shopify capital less than three years ago and is now originating nearly $100 million in quarterly merchant cash advances. To put this in perspective, Shopify generated $9 million in operating cash flow in 2018 on $41 billion in GMV. That cash flow number includes $95 million in stock-based compensation and nearly $6 million in Shopify capital provisioning. Generating profits out of being an ecommerce platform hasn’t gotten any easier since the days of Amazon, but as everyone in the space can’t invent another AWS with 40% margins these moves are not surprising. But Shopify capital definitely makes a lot of sense for Shopify as they are providing merchants with sales receivable factoring at very appealing economics for themselves. Advances are paid back at 10% of daily sales despite annual factoring fees in the 15% range. With visibility into merchant sales history effective APRs obviously are much higher.

And here is an example of how the product is marketed…

Shopify Capital gave Pistol Lake the funds they needed to keep their business growing, while helping them avoid putting up collateral, giving up equity, or spending their time filling out forms at the bank.

You can’t really fault Shopify for their marketing as they are simply trying to keep pace with the competition. Square, which introduced Square Capital in 2014, originated $485 million in small business loans across 72,000 customers last quarter. The ‘service fees’ from this close to $2billion annual run rate origination business are classified as subscription revenue by Square. Not to be left out, Stripe, is currently testing their own version of a cash advance called Stripe Advance. All three companies sport market caps in the $20-30billion range and are encroaching on each other's turf. Square via Weebly and their invoicing feature is trying to be more Shopify, and Shopify as it drastically ramps Shopify capital is trying to be more like Square. Stripe is sitting between the two and currently dabbling with elements that likely target both businesses. And then, there is good old PayPal, which was offering a lot of these services long before the new payment darlings showed up. Where do they stand in all of this? Well, eBay (NASDAQ:EBAY), which as far as I am concerned is still the only pure play ecommerce company to build a sustainable profitable business around their core offering, has now entered into a partnership with Square Capital for their merchants. Ironically, this has triggered issues with their former subsidiary PayPal, which still is sitting on plenty of loans originated to eBay sellers based on their exclusive relationship as their payment processor. Naturally, PayPal recently notified all these eBay sellers that they be out of compliance with their working capital loans.

So, where am I going with this and what does this all have to do with Brex?

Well, Square generated $256ml in ADJ EBITDA on over $80 billion in gross payment volume in 2018. Stock comp was $216 million. Square, with its current $30bl market cap and Shopify-esque 20x+ net revenue multiple, does not break out the ‘service fee’ it collects for originating Square Capital loans just as Shopify doesn’t disclose what it is earning of sales factoring. There is a good reason for this. Subscription revenue multiples for ‘tech’ companies are obviously a lot higher than loan service fee or sales factoring ‘interest’ revenue multiples of financial companies engaged in small business lending and servicing. Which brings me back to Brex….

With Adyen, Stripe, Square, and Shopify all currently sporting market caps larger than Deutche Bank (NYSE:DB), it’s hard to believe these 22-year-olds are going to disrupt anything with what is essentially a secured credit card for startups. Inferior economics against the old and new payment giants at this stage in the cycle simply mean much higher customer acquisition costs. Or does it? For all the hype involved here, Brex to me looks like a clever ecosystem play by startup investors. Ycombinator led their most recent round and was joined by startup heavy investors like DST Global, Peter Thiel, and Tiger Global. Brex also claims that over 50% of Ycombinator startups are customers. Basically, the startup ecosystem in the valley has grown so big that you can create one credit card company to try and capture recurring revenue derived from all your other related investment companies. Because at the end of day, startups spend most money on customer acquisitions costs, and in Brex, you’ve essentially created a business where you can drive that cost way down and consequently recapture and potentially multiply the value of your other investment dollars in a financially coated vehicle. And what Brex really looks like it's looking to exploit is making money of the startup customer acquisition ecosystem. For all the talk of Google/Facebook capturing 40c of nearly every VC $1 in ad spend on CAC, it seems Brex’s model is a tangential play on that theme.

Here is a brief breakdown of their loyalty reward program:

Amazon Web Services - $5,000 in AWS credits to be used over a year. The offer is only available to startups that have previously received fewer than $5,000 AWS credits through AWS, a VC accelerator, or other AWS-partnered organization.

Salesforce - $375 off an annual Salesforce subscription with a 25% subscription discount.

Google — $150 in annual Google AD credits

Twilio — $500 in annual credits

Carta — 20% of 1st year subscription cost

WeWork — 15% discount off of the list price for any new WeWork desk or office space for up to 6 months across all US locations (average of $5,000 in value for a typical office space)

Earn Points

7x on ride shares and taxis

4x on travel booked through the Brex travel portal

3x on restaurants

2x on recurring software/SAAS — Brex created this category which is apparently only trackable with Brex technology

1x on all other spend

All bonus categories are uncapped, with no limit on the amount of rewards you can earn. If you don’t use Brex exclusively, you’ll earn 1x on all purchases.

When you consider the fact that any established startup has already likely received some sort of sign-up incentives for using most of these services, Brex is really looking to play the part of channel funnel for new startup customer acquisition in the valley. They are also looking to collect fees from merchant partners by improving their ROI on marketing dollars spent acquiring customers via tailoring a rewards program around the ecosystem. Pretty clever, of course, once the startup funnel and customer acquisition subsidies dry up you are left with not much of a business model.

But Brex is not alone as far as startups that are booming by focusing on services to capitalize of the boom in startups.

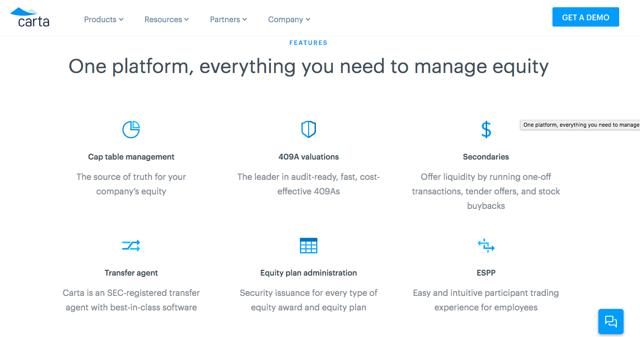

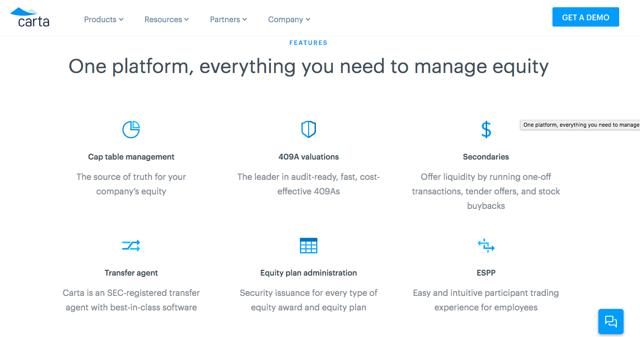

Carta

Carta has been around since 2012 and has seen its private market valuation explode in the past several months. After raising a series D of $80 million at $800 million in December, they are reportedly looking to raise $300 million at a $1.8 billion valuation this month. Carta offers a cloud service designed to streamline the once paper-based processes involved in managing a private company’s equity. This is what their landing page looks like…

Although Carta is not alone in this space, it’s the most notable standalone name, and its recent private market valuation explosion reflects the financial sectors recent plunge into tech land. Last month, and in its first notable acquisition since before the financial crisis, Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS) paid $900 million for Canadian-listed equity management competitor Solium, which manages equity for the likes of Instacart, Uber, and SpaceX. Solium is also notable for having bought Carta direct competitor Capshare in 2017. Morgan Stanley’s acquisition both provides it direct access to SAAS revenue in the private startup equity management space and opens the door for future Wealth Management access to a whole host of wealthy millennials. With stock-based compensation in tech booming and a long list of startups looking for more efficient ways to manage/value/trade private company equity, it’s no surprise that these types of business are now attracting a lot of interest. But when the broader bubble bursts, you can rest assured these types of investments will suffer the most because of the negative feedback loop.

And while surging interest in investments related to the unique financial characteristics of the startup ecosystem are the most obvious red flags, there are more traditional company moves in the financial sector that also are worth noting. Goldman (NYSE:GS) which bought the team behind credit card startup Final and the personal finance app Clarity Money in 2018, just launched their first consumer credit card with Apple. And let’s not forget Charles Schwab (NYSE:SCHW) which recently announced their robo advisor was switching from a AUM fee to flat monthly sub fee SAAS model. These headlines are not 22-year-old wunderkinds achieving eye-popping valuation type of news. However, when Goldman announces a credit card with Apple in the same week that Schwab and Burger King announce subscription- based products, I do take notice and start to think maybe we are a lot closer to the end of a cycle.

Back when Zenefits and Theranos were two of the hottest unicorns, I published a piece raising some mild concerns about Theranos business model. Now, I had no particular insight into the lab testing field, but a lot of elements of the story didn’t make much sense. Theranos’ pitch was preventative medicine and essentially early detection reducing healthcare costs and saving lives. However, all their marketing seemed to focus on the fact that a finger prick to eliminate fear of big needles, a nano-container to store the blood, and a compact machine to replace an entire testing lab were the secret sauce. The company never seemed to articulate how cheaper and more frequent access to my bloodwork was going to save my life. The role of doctors in interpreting the data, let alone how the benefits would be conveyed, were never a core part of the message.

Disruptors Whose Technological Innovation Is Access to Mountains Capital Become More Common

The whole Theranos thing fascinated me though because a while back I’d read about medical fraud tied to an electromagnetic pain device called the PAP-IMI that was marketed as capable of being able to ‘cure’ cancer and AIDS in the early 2000s. In researching that issue, I came across the story of the Dynamizer, a 1920s device that could diagnose any disease based a unique vibrational signature. The device, which was forbidden from being opened, made its inventor very rich, but obviously was a complete fraud. The mystique around the Edison reminded me of this story, and maybe this was part of Holmes intention. That being said what Theranos was doing was nothing new. They had raised a lot of capital to simply try and engineer/automate the blood testing lab into a box. Basically, rain money on a well-established workflow problem or seemingly non-evolving industry, and hope innovation comes out on the other side. There are presently two notable startups that seem to fit this bill….

Katerra

Katerra describes itself a “technology company redefining the construction industry.” They offer a vertically integrated model of design, material supply, manufacturing, logistics and assembly to shorten time and lessen the costs from building construction. You can call it modular building or pre-fabricated housing, but however you want to describe it right now, it’s called construction ‘disruption’. It’s been referred to as the Foxconn of construction and had articles in the WSJ with catchy titles like “Why you’d want to build a skyscraper like an iPhone”. Suffice to say it’s not short on hype. But the story is pretty simple. Factory automation and vertical integration will drastically reduce building time and costs. Sound familiar? And with a founder/COE in charge who used to run Flextronics and ironically Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA), this isn’t exactly the most surprising pitch. Let’s make homes like we make smartphones and pc’s!! Did these guys consider why there isn’t an MNC version of Apple, Dell (NYSE:DELL), or Samsung (OTC:SSNLF) in the homebuilding space yet? Did the concept of global economies of scale never occur to the homebuilding industry over the past 100 years? The answer to both of these questions seems to be no. But you don’t need to think too long about the problem. Zoning, labor, climate, seismology, cost effective raw material access, logistics, home ownership dynamics, design are all not standardized when it comes to housing. You can’t design a home in Cupertino, source the key materials to build it in Taiwan, assemble it in a mega factory in China, and then ship it to every major market on earth. Unfortunately, housing doesn’t work like contract electronic manufacturing, and Katerra has been finding that out.

Here are some critical highlights from a Summer 2018 Information Article on their issues:

The initial technology installed last year on the factory’s assembly lines didn’t meet executives’ expectations, people familiar with the matter said. Most of the machinery required several people to operate manually, rather than relying on automation. For instance, windows in wall panels are installed by people rather than a machine. That put the company behind schedule on how many wall panels it could produce each day, several former employees said. The company also has struggled to figure out how to install plumbing and electrical systems inside the wall panels it puts together at the factory, creating more work for on-site crews.

There have been other mistakes, former employees and people who have worked with Katerra said. For one California project, Katerra pre-assembled walls in its factory fastened with the wrong kind of nails that wouldn’t hold up under certain moisture conditions, a former employee said. For another project, delays in ordering material pushed work back several weeks. Some buildings have had issues with window leaks, other people said.

Other property developers working on projects with Katerra have had concerns about the firm’s performance, said a person in the real estate industry who has spoken with several developers. “Customers are frustrated that what they’re delivering isn’t good. Whole orders need to be canceled. [Katerra is] slowing down the process, as opposed to speeding it up,” the person said.

Growing pains are to be expected for a business like this, but that’s not really the concern here. The main problem I see is there is no broad stroke business model disruption embedded in Katerra’s business. Pre-fab housing is not a new concept….

That pamphlet is from the 1940s. Prefabrication and factory automation are not new things in housing. In Sweden, Lindback, an almost century-old Swedish home builder, produces modular housing components for multi-family housing projects at the rate of 20 units a week. And the entire manufacturing process is highly automated by tools from a Swedish company called Randek. Japan has also seen decent success with prefabrication models since the 1970s, but that hasn’t stopped the leading player in the space from needing to be bailed out multiple times over fifty years. So, Katerra isn’t exactly onto something new here. There are reasons prefabrication hasn’t taken off in North America. It’s not Sweden! Northern European labor costs are astronomically high, environmental regulations are super strict, and most people rent multi-family units vs. buy homes. Lindbeck’s current business model is suited to these cultural/regulatory/economic dynamics. So, copying a Swedish success story is not a good template for revolutionizing US housing construction. We haven’t cracked healthcare here let alone the ever-growing homeless problem. Maybe if AOC becomes president you can start counting on government supported social housing to justify the large upfront costs of giant prefab factories, but in today’s America, Donald Trump is President and Ben Carson runs HUD. Against this political backdrop and historical stigma around pre-fab housing in the USA, adopting a platform model to compete against subcontractors with cheap labor access paid per square foot of dry wall isn’t going to work economically except in a few areas.